This article first appeared

in Lonely Planet, "Africa on a Shoestring"

TOURIST VISA NO. 001

by David W. Bennett

I knew that Equatorial Guinea

was off the beaten track, but I didn't fully realize the remoteness

of the place until I looked down at my freshly stamped passport.

I had just been issued Tourist Visa No. 001.

Actually my presence in the country

was quite accidental. My original intention was to travel overland

from Cameroon to Gabon, bypassing Equatorial Guinea. Upon my

arrival in Cameroon, however, the authorities insisted that I

purchase an onward air ticket. Financial considerations and my

southward destination made me decide to take the weekly flight

to the Guinean town of Bata. My map showed it to be a mere 125

kms by road from the Gabonese border.

My

outdated guide book described Bata as a thriving commercial centre

with a population of some 30,000 people. I knew, of course, that

things had probably changed. Six months earlier, a coup had deposed

President Macias Nguema, one of Africa's most tyrannical dictators.

During his 10 year rule, many people disappeared, the country's

economy collapsed, and half the population was forced to flee.

This information didn't fully prepare me for what I found. The

centre of Bata was a virtual ghost town. The handsome Spanish

colonial buildings were boarded up, and the well maintained streets

were empty of both people and vehicles. I surmised that the refugees

had little reason to return here from the relative prosperity

of Cameroon or Gabon.

My

outdated guide book described Bata as a thriving commercial centre

with a population of some 30,000 people. I knew, of course, that

things had probably changed. Six months earlier, a coup had deposed

President Macias Nguema, one of Africa's most tyrannical dictators.

During his 10 year rule, many people disappeared, the country's

economy collapsed, and half the population was forced to flee.

This information didn't fully prepare me for what I found. The

centre of Bata was a virtual ghost town. The handsome Spanish

colonial buildings were boarded up, and the well maintained streets

were empty of both people and vehicles. I surmised that the refugees

had little reason to return here from the relative prosperity

of Cameroon or Gabon.

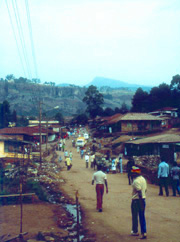

This conclusion did nothing to

alleviate my present predicament, however. Knowing there to be

no flights, I resigned myself to the possibility to having to

walk to Gabon. After about half an hour, I was surprised to come

upon an apparently well-populated thatched suburb. I say surprised,

but after travelling in Africa for a while, nothing seems that

surprising. I, therefore, did not find it strange to hear the

sound of a fifteen year old Beatles recording blaring from a

large thatched building. Nor did I find it that strange to enter

the building and find a well-stocked bar and about one hundred

dancing patrons, eighty of whom were young women. I am sure the

most bizarre event to occur that day was the entrance of a lone

white man, with a bag strapped to his back.

In any case, I settled down to

enjoy a few beers, answer curious questions and gather more information.

Amidst many offers of overnight accommodation, I was able to

ascertain that a vehicle would be making its weekly journey to

Acalayong, the southernmost town, the very next day

The next morning, a decrepit

pickup truck did, indeed, turn up. I thankfully scrambled into

the back with sacks of grain, baskets of live chickens and about

fifteen other passengers. Apart from one small village, there

was very little to see during the eight hour journey. The road

was in deplorable condition, practically swallowed up by the

dense jungle which closed in tightly on both sides. By the time

the truck wheezed into Acalayong, I was alone, my fellow passengers

having disappeared into the bush along the way.

Acalayong consisted of thirty

huts huddled on the shore of a broad estuary. At the shallow water's edge was beached

a flotilla, of hollowed-out log canoes; some sporting

outboard motors. After intense bargaining, one of the owners

agreed to take me across the estuary to Gabon. Soon, we were

under way, skimming over the water which occasionally surged

over the prow of the low sitting canoe.

We must have travelled a good

three hours before the engine sputtered to a halt. The estuary

had widened considerably at this point and the change in water

colour indicated that we were geographically in the Atlantic

Ocean. Apart from a few nearby islets, land appeared to be very

far away indeed. I was, therefore, greatly relieved when the

current carried us to one of these islets, rather than out to

sea.

To be truthful, when we landed,

I really was surprised. There was a village on this ½

sq. km. dot of land, and I was surely the first traveller to

ever visit it. Not only that, but the friendly villagers considered

me to be an honoured guest who had obviously come there to settle.

By nightfall, a reed hut had been constructed for me to live

in. Then I, and the entire village sat down to a feast of grilled

fish, manioc and copious quantities of palm wine. This was followed

by dancing, drumming, and drinking long into the night. It was

very late when I finally staggered to my hut and I did not have

the inclination to reflect on my onward journey. Were I feeling

romantic, I may have conjured up a multitude of exotic, Robinson

Crusoe-style scenarios. But sleep intervened and I awoke to the

reality of a buzzing outboard motor. And so it was, with the

entire village enthusiastically waving farewell, that the possessor

of Tourist Visa No. 001 finally departed Equatorial Guinea.

David W. Bennett ©

1985 - 2000